“The Transport Strategy will do nothing to bring about the type and scale of change that we need, and should be rejected. It is long on hope, short on ambition and does nothing for the climate emergency.”

The Transport Strategy for the South East does not address the urgent need to transform the way that we move people and goods in the region, especially given the climate emergency. Now is the time to re-wire our transport strategies and policies to put people and the environment first, ahead of the supposed need for continual growth.

The strategy persists with the same discredited transport ideology that has led to high levels of pollution and congestion. Its focus on ‘connecting communities’ fails to recognise the primary needs of the area’s residents, the majority of whose journeys are short and local. The strategy is particularly weak on addressing the needs of people in urban areas who suffer most from pollution, congestion and the other negative impacts of our motor vehicle-dominated transport network. Its enthusiasm for road upgrades consigns our population to more pollution, ill-health, conflict and a decline in quality of life.

This is a pity since the strategy has some good points. We welcome the recognition of a need for joined-up thinking and to plan at a regional, not just county level. We also applaud the emphasis in this document on people and places rather than cars. We agree about the need to replace the discredited ‘predict and provide’ approach with a determination to ‘choose a preferred future’ (page viii); and we strongly approve the ambition of reducing the need to travel at all (page x).

But the document does not follow through on these good principles. The emphasis is still on economic growth and jobs based on speeding up motor vehicle traffic.

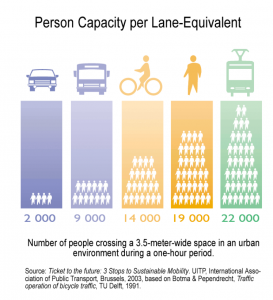

Instead, we believe, TfSE has a key responsibility to seize this opportunity to give leadership to the county councils which it represents. It should state clearly that high motor vehicle use is unsustainable and that priority must be given to walking and cycling for journeys up to 5 miles (68% of all UK journeys). Removing motor vehicle access to much of our towns and reallocating the space to walking, cycling and public transport is the quickest and most cost-effective way of unlocking the most benefits for the most people.

The plan includes several further flaws; some specific (pages 4-6); others more general (pages 2-3).

“The current approach to transport in the South East is unsustainable. The time for fundamental change is NOW.”

General flaws

1: SMART test failed

The plan has no budget or indication about how obtain funding, and lacks a statement about responsibility for its implementation:

Monitoring and evaluation: A mechanism for monitoring delivery of prioritised interventions, as well as evaluating outcomes related to the strategic goals and priorities, will be developed.

When, by whom and how will it work? Without answers to such questions no plan will be delivered.

2: National constraints not recognised

While having a Transport Strategy for the South East is a welcome step forward from planning at a county level, the lack of an integrated transport policy at national level will provide a handicap, unless power is truly devolved downwards from national level, as well as upwards from county level. e.g. will train operating companies in the region become accountable to this new body? Will responsibility for the strategic road network be devolved from Highways England? etc.

3: Key fact omitted

The strategy fails to recognise the key fact that 2/3rds of all journeys are less than 5 miles. It focusses mainly on long-distance travel and on solutions that improve links between business hubs in the South East – the minority of people’s journeys – rather than measures to improve short journeys within and around urban areas. Achieving modal shift for these journeys requires much lower funding, is easier to achieve and brings more benefits to individuals and the places where they live. Such modal shift would bring significant benefit to the longer distance journeys by reducing congestion at the start and end of many trips.

4: Wrong starting point

Despite the promise at the top of page viii to focus on ‘people and places’ the strategy is primarily about how to get people and goods and services from A to B. Instead, it should be about how to fulfil society’s and peoples’ needs. Here are two examples:

Example 1: in place of the trend of centralising services, which generates additional journeys, we need to consider whether providing services more locally could bring benefits, e.g. rather than thinking about how to get people to a specialist hospital for investigations and treatment, we need to consider how more tests could done locally – cottage hospitals, GPS, or at home – digitally transmitted to a specialist team, and results (especially if benign) communicated directly to the patient rather than a needless personal visit.

Example 2: rather than thinking about how the goods can get from a factory in place A to the port in place B eighty miles away, consider whether, with some changes to rail freight loading systems and some additional railway lines, they (and exportable goods from all the other factories in the vicinity of place A) could be got instead to a port only 20 miles away.

5: Too long and poor drafting

The document includes numerous passages of management-speak, waffle and statements of the obvious, such as…

‘Economic growth, if properly managed, can significantly improve quality of life and wellbeing. However, without careful management, unconstrained economic growth can have damaging consequences or side-effects.’ (page xi) or

‘Motorways are strategic significant roads that move people and goods rapidly over long distances.’ Its length, plus numerous typos, such as ‘unconstrainted’ (page xi) and ‘strategicy’ (page 60), constitute a disincentive for people to read it and take it seriously. It should be cut to a short statement of principles followed by a concise, costed plan with maps, a timetable and responsibilities for implementation, truly a ‘SMART’ strategy.

Specific flaws (a few examples)

| Page | Text | Comment |

| v | Foreword by Cllr Keith Glazier Chair of TfSE The first step on this journey is a simple one; we must make better use of what we already have. Our road and rail networks in the South East may be congested but we know that, in the short-term, targeted investment to relieve pinch-points alongside new technology like digital railway signalling are the best and most effective ways to address short-term capacity and connectivity challenges | No. ‘targeted investment to relieve pinch-points’ means schemes such as the Arundel bypass illegally carving its way through a national park and destroying ancient English woodland in order to ‘save’ motor traffic a few minutes. Following this failed policy for the last forty years and building more roads simply brings more traffic. We need to reduce the number of vehicles on the road by dis-incentivising their use, not catering for more of the same. The foreword fails to recognise that 2/3rd of all journeys are under 5 miles (DfT figures) and so comfortably do-able by bike if safe, comfortable infrastructure is in place. Focussing first on more active travel for short journeys as a first step is the single, most effective and low-cost way of reducing congestion and pollution, and improving the residents’ health and well-being. |

| xi | Key principles for achieving our vision This page includes several good principles, but… ‘Transport for the South East has developed a framework that applies a set of principles to identify strategic issues and opportunities in the South East, in order to help achieve the vision of the Transport Strategy.’ | …is meaningless waffle |

| xi | ‘Economic growth, if properly managed, can significantly improve quality of life and wellbeing. However, without careful management, unconstrained economic growth can have damaging consequences or side-effects.’ | …patronises the reader with somewhat sanctimonious statements of the obvious, and should be expunged. |

| xiii | Prioritise vulnerable users, especially pedestrians and cyclists, over motorists | Yes, but the proposals give no such priority. Otherwise the word ‘bicycle’ would appear more than once in 101 pages and road safety would the top priority. 165 people died on roads in the South East in 2018 and 3,000 were seriously injured, 1/3 of whom were pedestrians or cyclists. Safe, segregated infrastructure will have to be provided and pedestrians, cyclists and other vulnerable roads users cannot be expected to ‘share the road’ with 2 tonne (and above) motor vehicles. |

| xiv | Priorities for investment New roads, improvements or extension of existing ones should be prioritised in the short term but become a lower priority in the longer term. | Not even the short term. Such an approach merely increases traffic by ‘induced demand’ and makes the task of reducing traffic more difficult. Better to face the inconvenient truth now. Infrastructure to enable walking and cycling, which once implemented would result in a 15-20% modal shift away from motor traffic for a minimal investment compared with road-building, is not mentioned in the list of priorities for investment. Since 2/3rds of all journeys are under 5 miles it should be the number one priority. |

| xiv | Public transport access to airports is a high priority and, in the case of Heathrow Airport, must be delivered alongside airport expansion. | Are we really still planning to expand our airports? Have the authors of this plan not read or understood the IPCC’s latest report? |

| 4 | How this Transport Strategy was developed | No mention of considering best practice from other countries. Taking evidence from a car-dominated society simply leads to more cars. |

| 46 | 2.71 In general, many of the long distance footpath and cycle routes in the South East appear to be better suited to supporting leisure journeys (e.g. longer coastal routes) rather than connecting large population centres together. There are some notable gaps in the National Cycle Network (e.g. West Kent and Thanet) and the quality of cycle routes varies enormously across the network. While some sections are well surfaced and clearly lit, many other sections are unsuitable for night-time journeys and/ or would be hazardous to use in poor weather. Furthermore, some Major Economic Hubs are not served by the National Cycle Network at all (for example, the Blackwater Valley). This suggests there is scope to further expand walking and cycling infrastructure to encourage more sustainable forms of transport, particularly within and between the larger urban areas in the South East. | Leisure routes are largely irrelevant to the serious matter of transport and this comment should be deleted The sentence “This suggests there is scope to further expand walking and cycling infrastructure” shows a total lack of political will to adopt one of the most important measures to solve the problems of congestion and pollution. Instead the text should read: ‘The South East, in common with the rest of England, has few cycleways which would pass the 12-year-old daughter test. Most journeys require cyclists to share the road with heavy, fast-moving motor traffic with no protection at all. Some have painted cycle advisory lanes which are totally ineffective or mandatory cycle lanes which are largely ineffective. Well-constructed segregated cycleways with priority at side junctions are almost unknown. As a result very few people make even short journeys by bicycle’. At a rough average of £1.45m per kilometre (see 2017 DfT report) we could build 5,000 km of top quality cycleways in and around our urban centres in the South East for £7.25bn, less than half of the DfT’s and the constituent county councils’ annual spend on roads. |

| 78 | 4.18 Local journeys are short distance journeys that are typically undertaken at the beginning or end of an individual journey to or from a transportation hub or service to a destination. They include first mile / last mile movements that form an important element of other journey types described in this strategy. | No. While some local journeys are part of a longer journey, most are short local journeys to go to work, to the shops or to school. It is this misconception that undermines the whole document with its focus on corridors, strategic routes etc, missing the point that 2/3rds of all journeys are under 5 miles in total. |